As the Federal Reserve navigates its next moves on monetary policy, a growing debate has emerged about whether officials might be overcorrecting for inflation. San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly recently offered a warning that's getting attention: don't fight yesterday's battles so hard that you kill tomorrow's opportunities.

A New Debate Inside the Fed Takes Shape

Right now, investors and economists are split on where the Fed goes from here. Is the tightening cycle basically done, or does inflation still pose enough risk to stay cautious?

A recent statement adds another layer to this conversation—Daly's caution about not repeating the policy mistakes of the past by leaning too aggressively in one direction.

Her warning highlights a delicate balancing act the Fed must perform as it tries to avoid both past mistakes and future missed opportunities.

Daly's Message: Learn From the Past, But Don't Fear It

Daly made it clear that while policymakers need to remember both the inflation chaos of the 1970s and the post-pandemic price surge, they also need to keep the bigger picture in mind. Her key point? "We don't want to work so hard to not be the 1970s that we cut off the possibility of the 1990s." In other words, over-tightening now could choke off jobs, investment, and productivity growth—the exact ingredients that fueled the booming '90s economy.

This tension gets clearer when you look at two historical charts that paint very different economic pictures.

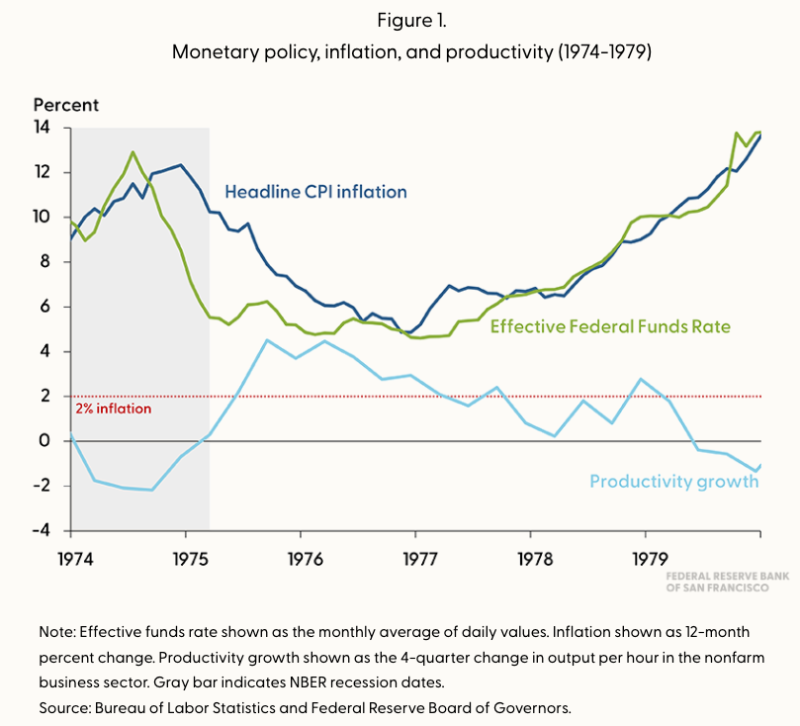

1974–1979: When Inflation Overpowered Policy

The first chart covers 1974–1979, showing exactly why the Fed stays nervous about easing too soon. Headline CPI inflation shot above 12%, consistently outrunning interest rates. The effective federal funds rate lagged behind inflation, creating negative real rates—a major reason why prices kept accelerating. Productivity growth crashed, even turning negative several times, signaling deep structural problems. The shaded recession in 1974 shows how this instability directly triggered economic contraction. This era remains the textbook case of the Fed "falling behind the curve."

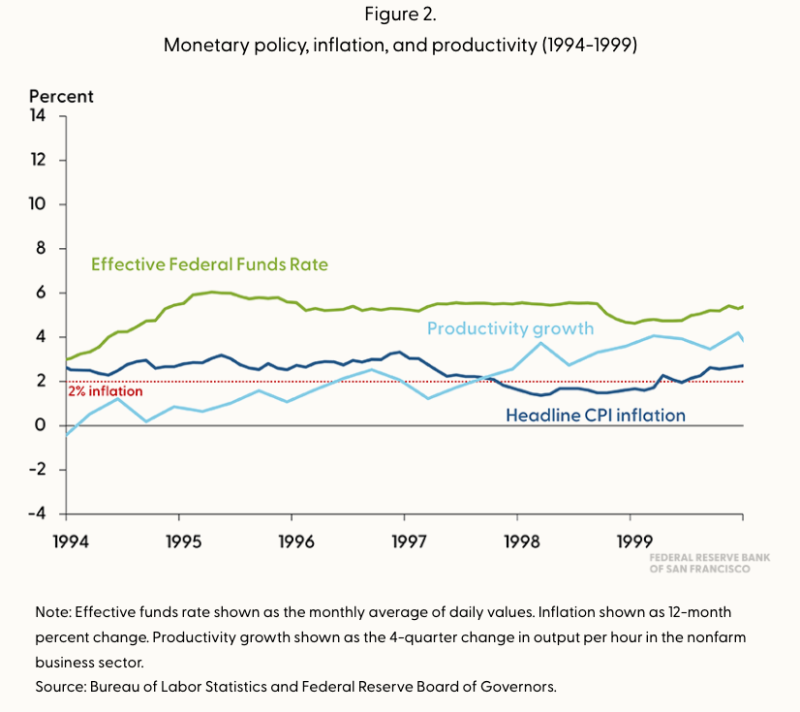

1994–1999: The Model Daly Doesn't Want to Lose

The second chart, covering 1994–1999, tells an almost opposite story. Inflation stayed stable around 2%, right in line with the Fed's target. Productivity growth picked up momentum, especially after 1996, driven by tech adoption. Interest rates were positive in real terms but not overly restrictive, letting the economy grow without overheating. The result? Robust job growth, strong GDP expansion, and rising wages. This period is widely seen as a "Goldilocks" era—everything balanced, productive, and stable. Daly's warning is that a policy too obsessed with crushing inflation at all costs might accidentally prevent the economy from reaching a similar sweet spot today.

Why Daly's Warning Matters Now

Her timing matters. Here's where things stand: inflation has dropped sharply from its post-pandemic peaks, productivity has improved thanks to tech adoption and post-pandemic restructuring, labor markets remain solid though gradually cooling, and growth has held up better than expected, raising hopes for a soft landing. The charts back up Daly's view—today's economy looks more like the mid-1990s than the mid-1970s, but only if policy stays balanced.

What Investors Should Watch Next

Key indicators to track:

- Productivity Trends: A sustained rebound could justify looser policy without sparking inflation

- Headline CPI Stability: Any re-acceleration would bring back 1970s concerns

- Real Interest Rates: If they stay too restrictive, they could suppress investment and hiring

The contrast between the volatile 1970s and the balanced 1990s shows the choice facing policymakers right now. Daly isn't saying to ignore inflation risks—she's saying don't fight the last war so hard that the Fed ends up strangling a modern, innovation-driven expansion. For investors, the message is clear: the next phase of monetary policy won't just be driven by inflation numbers, but by the Fed's attempt to balance caution with opportunity.

Sergey Diakov

Sergey Diakov

Sergey Diakov

Sergey Diakov